Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

If you’re an early-stage medtech founder and your first instinct is to jump straight into prototyping… you’re already on the same path that terminates 90% of medtech startups.

The reality is that founders who win don’t start by building—they start by defining precisely what must be built.

Without this scaffolding, your company will collapse under scope creep, unclear requirements, and investor uncertainty.

I’m Vlad. I’ve spent the last half a decade working across medical device university spinouts, startups, and a Fortune 500 company. And along the way, I’ve noticed the same painful pattern:

Brilliant ideas crumble because teams did not spend sufficient time building their foundational documentation.

In this article, I will outline two essential documents you must establish before building a prototype, and I will explain how they protect your commercialization path.

My promise to you is that if you make the conscious decision to develop the documentation I outline, your development schedule will be much more robust, your task prioritization will become significantly clearer, and your investors will gain confidence in your vision – because it is grounded in truth, not guesswork.

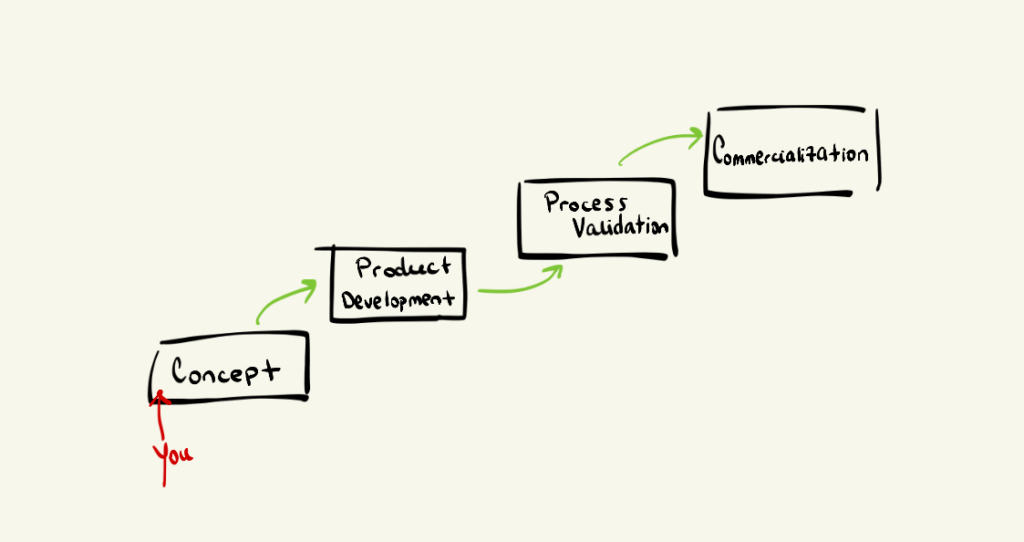

Right now, you are at the very beginning of the medical device lifecycle, inside the conceptualization phase.

And that’s such a wonderful feeling! You’re at the dawn of a potentially revolutionary technology. Your mind starts to fantasize about :

… as you become a thought leader in this wonderfully dynamic industry.

And, to no one’s surprise, all you want to do is start building this technology.

But that mentality is like Medusa: charming and enticing until the final moment – when ruin strikes.

Let me illustrate how this scenario plays out 9 out of 10 times.

You will start building – one feature after another, one improvement after the next – following no requirements and no constraints. You are simply relying on the project’s initial trajectory. And on paper, you are making tremendous progress.

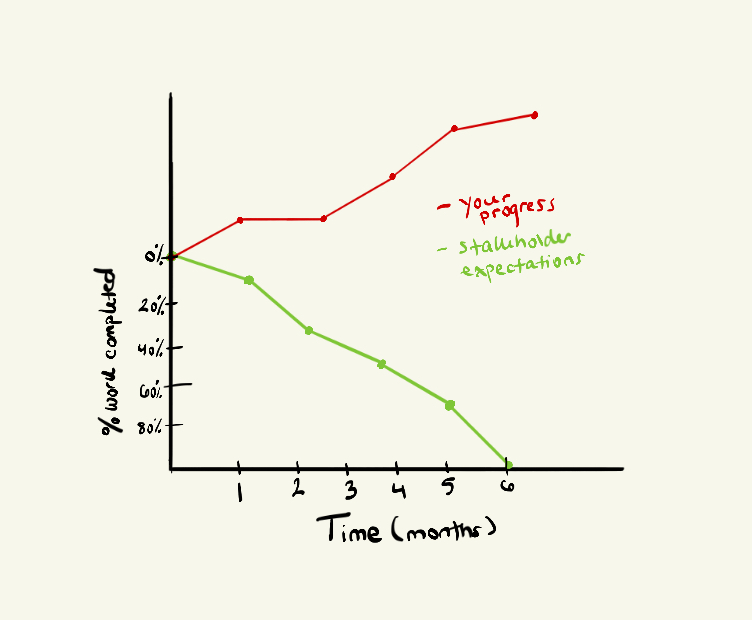

Six months later, you snap out of the prototyping trance and decide to share your progress with the stakeholders, to get their feedback on your promising work. And, well, this is where Medusa strikes. Take a moment to analyze the burndown chart below. For those unfamiliar, a burndown chart is a graphical representation of the percentage of completed work over time.

As you overlay your work against your stakeholders’ expectations, you will notice a stark misalignment.

And this will become increasingly vivid as the stakeholders share their thoughts:

“This isn’t what we envisioned…”

“Why are there so many features?”

“This won’t fit in the laboratory we are currently working in…”

“The device does not automate the intended workflow…”

So, following this gutting conversation, you realize that

And as if matters couldn’t get any worse, you need to break the news to your investors, and :

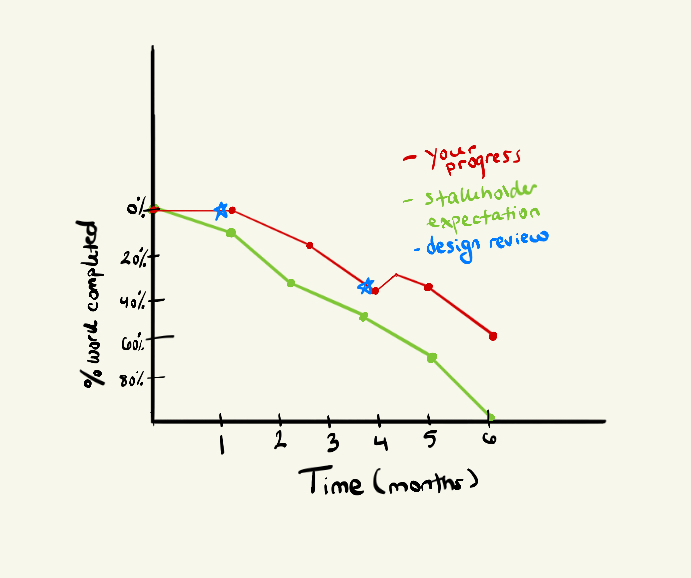

Compare that to the version of you who spent the first two months defining the project’s trajectory, alongside your stakeholders. All while developing the device in parallel and sprinkling critical design reviews along the way.

After six months, the final stakeholder review occurs, and what you can see is alignment – not perfect, but certainly more promising than the previous founder. Moreover, the slight delay is justifiable: there may have been sudden changes in the process that needed to be accounted for during development, or a high-risk item was identified, and the team and stakeholders reached a consensus to mitigate it, thereby improving the technology’s safety and efficacy.

Now, the tone of the conversation is understanding, not judgmental; supportive, not damning; hopeful, not discouraging.

Stakeholders will back your decisions.

“It was a good idea incorporating that feature, maybe it’ll help us capture more of the market”

They will offer solutions to keep your project afloat.

“How can we help you make sure you can hit this next milestone? Do you need more engineers, consultants?”

Most importantly, their confidence and trust in you will increase as they begin to inquire about the future.

“ What does the next stage of development look like?”

“ Any ideas for a next gen device?”

So, which founder are you more interested in becoming? The one who strikes doubt in the hearts of your patients, coworkers, and investors? Or, the one who induces confidence, hope, and anticipation?

What exactly was the difference between the two founders?

Luckily, this distinction can be outlined in two critical documents.

Firstly: the User Requirements Specification (URS). This document captures your end users and customers. It outlines their pain. It broadly defines the end user’s expectations for the technology’s functionality, performance, features, and dimensions.

An example user requirement looks something like this.

“The scientist must be able to automatically transfer a solution from a bag to a culture vessel.”

“The scientist must be able to efficienctly and accurately transfer the solution from a bag to a culture vessel.”

At this stage, the document structure should be simple, leveraging three categories:

In other words, you must be able to distinguish among the requirements; the importance of this will become more apparent in future discussions. You must include a description of the need; the rationale for this is evident. And, very importantly, you must identify whether each need is a “must have” or a “nice to have”? Since you are in the early concept phases of your medical technology, understanding what needs are a “must-have” and which ones are a “nice to have” is absolutely critical. It’ll save you months of development, significant capital, and help you stay focused on the aspects of your design that provide the most value to your stakeholders.

To get you started, I compiled a few questions that should ease the uncertainty of brainstorming your user needs:

So, I urge you to start developing this document as early as you can. I urge you to spend the necessary time outlining every detail, truly understanding your users and customers, their pain, and their expectations. It’ll guide your every decision from this moment on.

Now, I have good news and bad news. The good news is that you now have a comprehensive list of needs. The bad news is that they are useless for the actual development of the technology until translated into the following document – the Product Requirements Document (PRD). This is where the real engineering work begins.

So where do you start?

To begin populating the PRD, you will convert each of the requirements in your URS into engineering specifications. These engineering specifications will, from this point on, be known as your design inputs. The term “design inputs” will be a recurring theme throughout your career in med device, as they will drive the majority of your downstream verification, validation, FDA Clearance, and commercialization path. However, at this stage, all you need to know is the following

What does this conversion actually look like in practice?

Take the above example,

“The scientist must be able to efficienctly and accurately transfer the solution from a bag to a culture vessel.”

A direct translation of this into a PRD format will look something like this :

“The device SHALL dispense a solution at a maximum rate of 2000ml/minute +/- 10ml”.

As you can see, the high-level efficiency need is paired with a design input of “2000ml/min” and the accuracy requirement is linked to a “+/- 10 ml” tolerance.

It’s important to note that med device development is not entirely sequential. In other words, if you want to be efficient, you can not afford to wait three months to complete your user requirements, then start your product requirement document.

A more realistic approach is to start outlining your user needs and concurrently outline the design inputs for those needs. Also, in parallel, you will want to start developing your prototype to meet your outlined criteria and make adjustments as needed.

So, we’ve explained the major contributor to medtech startup failure, the build-first mentality, and identified two critical documents that will save your startup from ruin. Those are the User Requirement Specification and the Product Requirement Document. Remember, start documenting early, be detailed, and be patient. Your effort and thoroughness will pay off later on.