Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Every early-stage medical device startup I’ve worked with has either overlooked risk analysis entirely or treated it as something to “handle later.”

Here’s the hard truth:

Failing to understand and address your technology’s risks early isn’t a shortcut – they will resurface later, at the expense of your regulatory submission and commercialization.

If you are an early-stage med-tech entrepreneur still in the conceptual phase, you’ve found this article at exactly the right time. But do not skim it. Learn and apply the concepts here if you want the most efficient path forward.

If you are approaching the point where a Quality Management System must be implemented, you are behind, and you should expect development timelines to slip as a result. However, although the best time to plant a tree was a year ago, the second-best time is today, so you should not let this oversight stop you from execution. On the contrary, you should plant the tree and begin watering it immediately.

In medical device development, risk is a function of :

The severity of potential patient harm, and the probability that harm occurs, as a result of foreseeable events associated with your technology.

In other words, risk is the predictable consequence of how your device can fail, how those failures manifest in the real world, and how patients are ultimately affected.

To evaluate and control risk, medical device development relies on two distinct yet interconnected analyses:

Each looks at the same system from a different direction. Neither is sufficient on its own.

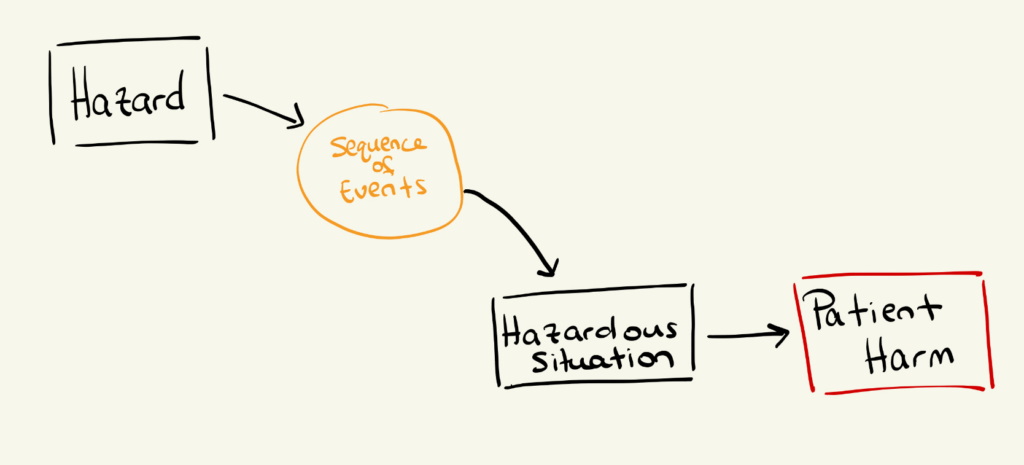

Hazard analysis outlines the pathway for how a hazard can lead to patient harm. Its purpose is to identify unacceptable patient outcomes and understand what sequence of events could plausibly create the conditions for those outcomes to occur.

At its core, hazard analysis connects three elements:

In practice, hazard analysis asks:

Because this requires clinical judgment, hazard analysis is most effective when performed or reviewed by physicians, clinicians, or subject-matter experts familiar with the intended use of the technology. Clinicians often identify hazardous situations that engineers miss—not due to an engineer’s lack of skill, but rather due to a lack of exposure to real-world clinical workflows.

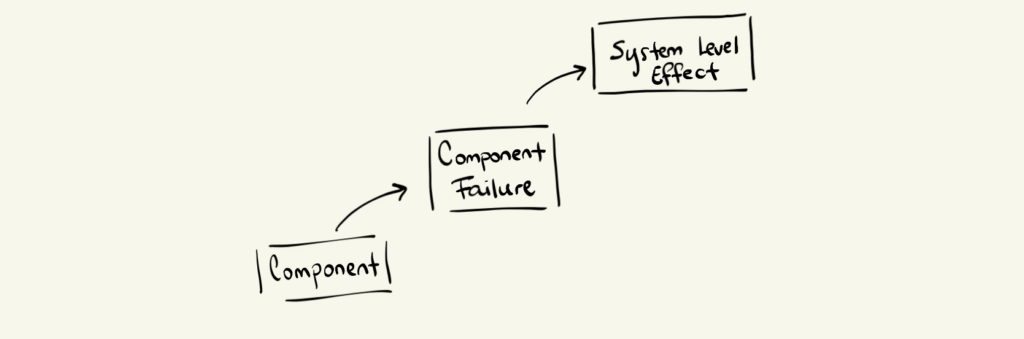

Failure Modes and Effects Analysis takes the opposite approach. It begins at the component or subsystem level of your technology and progresses upward to system-level consequences.

In an FMEA, engineers examine:

Typical FMEA questions include:

On its own, FMEA tells you how the device can fail—but not whether that failure is dangerous to a patient.

That connection comes from hazard analysis.

Now this is where the magic occurs!

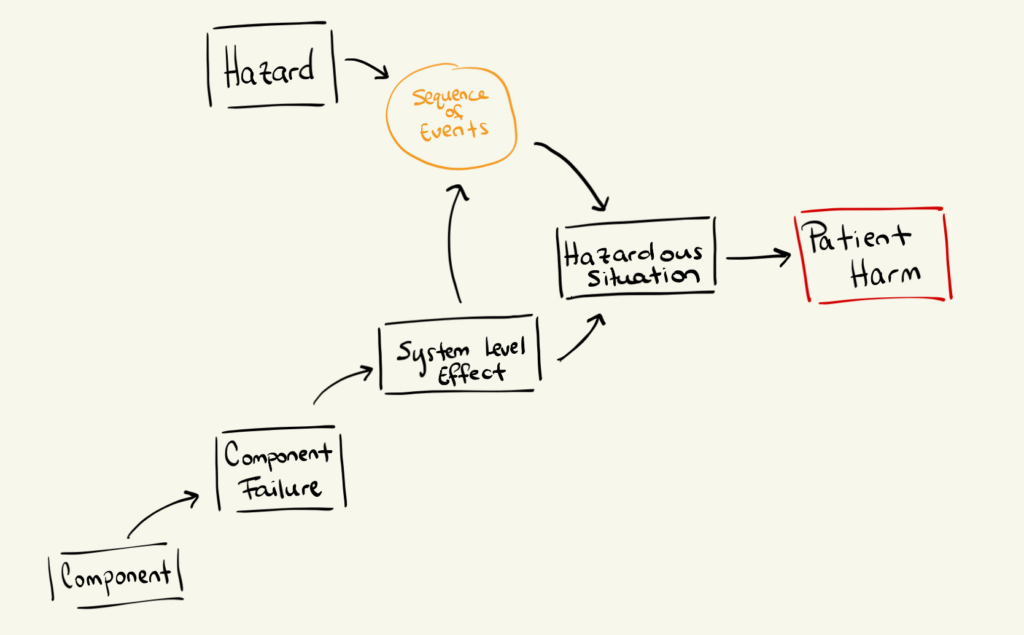

Hazard analysis and FMEA are separate activities, but they are intentionally linked.

They meet at the point where a system-level effect creates a hazardous situation.

Here’s a useful way to visualize this relationship :

As I briefly alluded to earlier, a complete and thorough risk analysis demands both Hazard analysis and FMEA. Otherwise, you will fall into two distinct categories:

Both of these scenarios carry significant patient risk, and as medical device developers, your primary responsibility is to improve patient outcomes, not deteriorate them.

However, when executed comprehensively :

Together, they form the backbone of safe, defensible medical device development, and give you, the design authority, a development roadmap for a safe and compliant technology.

Imagine you are developing a system that delivers fluid from a bag to a cell culture vessel using a pump. This fluid sets the final cell concentration of a therapy.

For proper treatment:

Anything outside that window compromises therapy quality or patient safety.

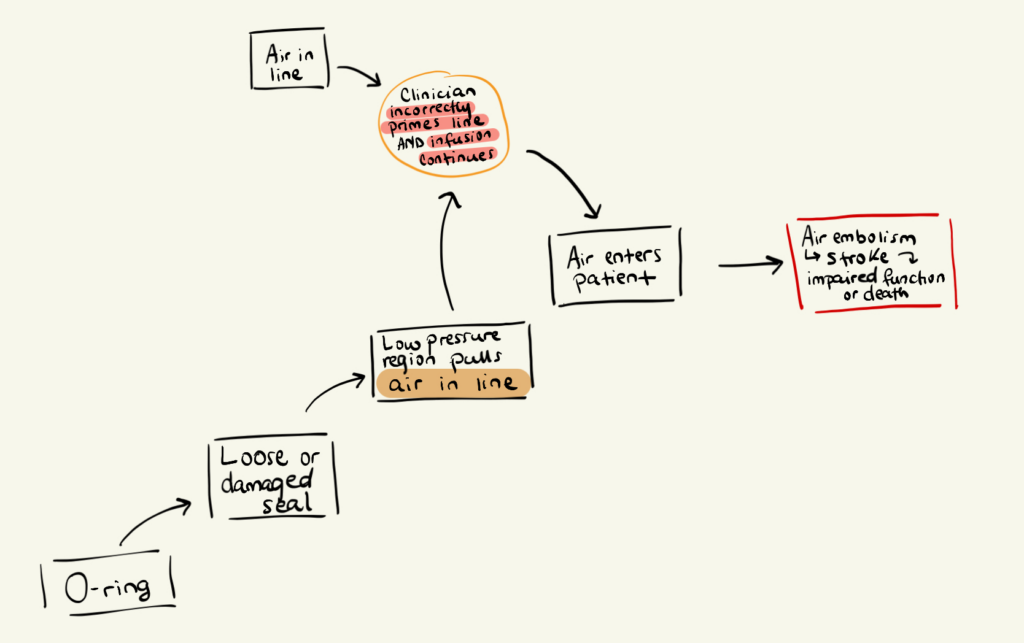

Step 1: Identify a Hazard

Air in line

Step 2: Identify the sequence of events

A clinician incorrectly primes the system, leaving air bubbles in the line; The infusion proceeds.

This step is often overlooked, but it is critical. If you do not explicitly describe how a hazard becomes a hazardous situation, you will miss severe patient risks.

Step 3: Define the Hazardous Situation

Air enters the patient.

Step 4: Identify the Harm

The patient suffers an air embolism, which may lead to stroke or death.

At this point, you know that air in line represents a serious hazard with catastrophic potential if not controlled.

Now you analyze the system bottom-up.

Step 1: Identify a component

O-ring

(Its function is to create a seal that prevents liquids from exiting and contaminants from entering.)

Step 2: Identify a failure mode

Loose or damaged seal.

Step 3: Identify the system-level effect

A low-pressure region forms, pulling air into the fluid line.

Here’s the key connection:

A component-level failure (O-ring seal) creates a system-level effect (air drawn into line), which enables the hazard previously identified in the hazard analysis.

This is how FMEA and hazard analysis reinforce each other.

At this stage, your task is simple:

If you cannot draw a clean line from component failure to patient harm, your risk analysis is incomplete.

A common mistake is believing risk analysis must be exhaustive to be valuable.

However, early-stage risk analysis is not about completeness.

It is about directional correctness. Every hazard or failure mode you identify and mitigate brings you one step closer to a safe and effective product.

Additionally, refrain from making the excuse not to begin risk analysis until you have a prototype. Waiting until then guarantees your most dangerous risks will surface at the most inopportune times.